The date was September 12th or 13th. It was the day after I had the conversation recounted in my prior entry. My calendar informs me that these dates were Monday and Tuesday, respectively. It seems likely that the day was Monday. I had yet to formulate a clear plan of traveling to Indianapolis when I rung off. However, it was clearly the most important thing for me to do.

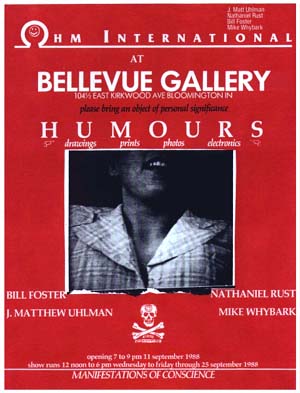

Those of you who know me also know that I have never had a driver’s license, and have only experienced two truncated bouts of car ownership. Therefore traveling on my own was not a viable option. I was also consumed with the unexpected responsibility of the emotional weight of the little shrine to my sister we’d included in the art opening. Understandably, I felt reluctant to ask others to perform the gallery-watching duties which accompanied shows at the space, a co-op called the Bellevue Gallery. Additionally, school had just started and i think I had some plan of getting advance assignments to cart up to Indy the next week.

In hindsight, it seems clear to me that in some way I was also avoiding an unpleasant duty, by not having traveled up sooner. Not that staying in Bloomington really succeeded as an avoidance, mind you; the fact, noted yesterday, that Suzy’s accident was among the first tragedies to ever strike our extended bohemian cohort meant that my family became a lightning rod for a wide range of people, seeking the same things any human seeks when confronted by the unknowable pain of loss and grief.

I have no recollection of the means whereby I reached the hospital in Indianapolis. It’s only logical to assume I was able to take advantage of a proffered ride, but I do not recall, precisely, who I traveled with. I know that at the hospital, Joey and Kara, and, I think, Jennifer were there, as well as others: Terri and also Burd, I think; Seth; my parents, obviously. I know there were more there, but my memories of my visit begin with my uncertain entry into the actual care facility of the intensive care unit.

The unit was laid out in ring around a central desk, a layout common to contemporary medical facilities where immediate patient access is a prerequisite. By stationing the staff centrally, it means the staff travels the same distance in the event of any given patient requiring urgent attention.

In my recollection, it is nighttime; the lights are dim, and the overheads in the unit are off, so that the light reflects off the polished buff tiles of the floor, and soft or intense pools of light mark the various locations that medical personnel are performing their tasks or have paused for the duration of the visitation schedule.

The fact that it is nighttime suggests that this is late Monday evening. So does the presence of friends who were still in high school, who presumably would have driven to Indianapolis following dinner at home.

I don’t know if there was a monolithic visitation schedule for the unit or if it was staggered; I suspect it must have been staggered, because I did not note other families moving in and out of the unit while I was there; this approach would also minimize the number of stressed out civilian visitors that the staff would need to keep track of at any given time.

At any rate, approaching the central desk, I quietly ask where my sister might be. I am alone, as just as at the emergency room, only one visitor at a a time is permitted. My voice cracks with emotion and fear that I am unaware of until I hear it. I look back at the double swinging doors of the entrance to the area, and I can see Joey and Kara’s face, peeping in. I wave, an acknowledgement and a farewell, because my sister is in a room out of line of sight from the windows in the door.

I may have been led into her room, or I may have simply entered at a direction from the duty nurse. The door to the room my sister is in is open, as, locally, are most of the doors to patient’s rooms. It’s about twelve hours since that troubling pressure spike was measured in my beautiful, wild sister’s still head. In twelve hours they will measure her interior cranial pressure again, in preparation for an EEG to determine her level of brain activity. I’m confident that the results of this test will be positive as I pause in the doorway, peering into the dark room, waiting for my eyes to adjust.

The darkness of the room ins bluish, and the light near the head of my sister’s bed is warm and yellow. Her arms are exposed atop the bed, and the back of the bed is lifted up by about eight or ten inches. I’m sure that the air around me is filled with the whooshes, pings, and creaks of the life support apparatus but I do not hear it. The sloppy tape and iodine stains are gone. So is some of her hair. There’s more tubes. Something’s different – she looks,uh, puffy, somehow. Not enough to really identify any specific change. Maybe it’s the drugs.

She lies still. I quietly approach the bed, a touch unsteady, reaching out for her hand.

“S-suzy? Are you – no, of course you’re not OK – uh I, uh, the opening went well – you have no idea how uh how, um. How many. Lots. Everyone’s thinking…”

I take her hand. It is limp. It is slightly cool. It is inert. It is uninhabited. It is an object. It is abandoned. It is empty. It is light. It is heavy. It is clammy. It is hot. It is painful to hold.

She’s

fucking DEAD!

DEAD!

D E A D!

I have clear, unambiguous memories of some of the next few moments. I doubt I can fully express them in this medium. I immediately, and completely, lost all self control. I flung myself across the mechanically-maintained remains of my sister, sobbing uncontrollably. I believe I must have repeated, possibly yelling, what I am sure is the first word I ever learned: “NO!”

“NO!”

“NO!”

I don’t believe that continued for very long. I held her to my head, pressing her against my body, stroking her matted hair, sobbing and sobbing and sobbing, the muscles of my mouth frozen, aching, into a grimace I was utterly powerless to control or change even as facial cramps increased my already considerable discomfort. I frantically rubbed her shoulder and head, expressing my depth of adoration too late too late too late for ever for the rest of my life for ever gone.

Gone. Gone.

My sister, my love, my life; the yes to my no. We lived together the first summer after high-school and got the fighting out of the way then; after that, she was the closest person the world to me, who knew me, as, well, a sister. I knew when I was a child that I would never have kids; the incredible force of my negativity is something that no child should – or will – be exposed to in a full-time parenting environment.

My sister was the inverse of this, an earth-mother punk rock force of nature whose drive and intellect were on a par with my own. I recall violent teenage disagreements in which our combined hormonal misery and absurdly high intellects confounded every parental effort to mediate or rectify. I sometimes wonder what it was like for my parents, with two such iconoclasts competing with one another and the world at large for our own slice of adolescent self definition. Exhausting, I’m sure.

She had long-term struggles with clinical depression, and had been on and off medication for it for some time. This was pre-Xanax, and I think that the first drug she was on was Lithium; watching her incredible mood swings as she tapered off that drug made me permanently mistrustful of the psychiatric pharmacopeia. For the most part, however, that was behind her.

She’d chosen the inverse of my life, traveling and studying the world over. Between her high-school graduation (a year early, in my class, 1984) with a 4.0 GPA and this terrible night in September, a bit more than one month shy of her twenty-second birthday, my sister had studied in the Semester at Sea program, in which college students circle the globe in a cruise ship which is employed as a traveling university, lived and studied in Liege and Brussels, Belgium for, I believe, a year, and again for two years in Shanghai, China. She spoke fluent French, and was a much more diligent student of that language than I have ever been.

Generally speaking, where I can be counted to turn my intellectual and energetic resources to that which is discounted or credited as dangerous in the received wisdom of our culture, my sister applied herself diligently in the ways we’re encouraged to as youth. But for her it was in order to escape, and drove her to seek what she sought – the authentic, I believe – in other cultures, less homogeneous than ours, matured without the shade of endless carports and malls and cheap, mass-produced industrial goods.

I strove to demonstrate to her that authentic, organic culture – the culture that ultimately generates everything worthwhile and full of flavor in life – is inescapable, and all around us, and merely because much of it is ignored as unmarketable does not mean it’s not available for consumption and participation. Eventually, I am so very happy to recount, she accepted this view and turned her boundless energy and razor wit to exploring this in Bloomington, in the field of my friends and in the company of our peers.

That summer (or perhaps the summer before), for reasons I can only describe as of conscience, she single-handedly started a volunteer-run recycling pickup cooperative, at least three years before Bloomington established any sort of municipal recycling program. That core group of volunteers was nobody special (I mean in the world’s eyes, as I am describing some old and dear friends – you’re special to me and also to Fred Rogers, kids!), not particularly political, and basically simply composed of a subset of our friends who, via my sister’s inspired prompting, got organized. Their successful functioning was instrumental in providing a spur to the city government in finally beginning to establish municipal recycling in Bloomington.

But back to our story.

I stood outside the ICU, looking in at the figure of a young man, who, weeping, and staggering in the depths of his misery stumbled blindly, weaving, heaving, shaking, one hand to his tear-blinded eyes, the other outstretched in a gesture of both warding and seeking. He dragged his feet; he paused; his body warped and twisted under the gusts of his grief.

It took him an endless moment to cross the open space of the ICU; watching him was like watching an automobile accident. The people near me, crowded by the door, burst into tears all at once, crying out the name of the young man they watched in horror.

“Mike! Mike! What is it, what happened?”

“Do you need help?”

“Is Suzy OK?”

“What’s going on, do you need a doctor, should we call someone?”

He pushed through the doors if the ICU into their midst, and I was mobbed by the concerned teenagers as I stood sobbing helplessly, wracked, great creaking loud gasps of air forcing my body into convulsive cycles and making it impossible to even mouth the formula the situation requires. I was not OK.

My emotive disarray had a kind of infectious effect on the people nearby, for, I’m sure, a variety of reasons. The increasing waves of fear, tears, and concern both rippled out from us and drew people to us, as I stumbled with the small knot of onlookers into the waiting area where the entire crowd of people who were paying court to my dying sister and our parents had assembled.

I have no clear memory, again, of the journalistic details of the situation. There may have been a total of ten people there in addition to my immediate family. There may have been as many as twenty all told. I do not know.

As my sisters’ crisis became the eye of a gathering storm of emotional concern among our peers, certain qualities that my family possesses began to accidentally shape the form of the concern and attention that was focused on us. First, we’re all good in a crisis. It takes events that are difficult for me to anticipate to powerfully and continually disrupt our ability to reason and think ahead, analytically seeking the optimum outcome. Second, my parents are as verbally facile as I am, and the combination of these skills means that our communications with those around us at this time became something unexpected.

Although I accept and treasure the form it took, I also regret that we did not have the foresight to create sufficient privacy for ourselves. As will be seen, we spent an inordinate amount of time helping others to manage their grief, something which fairly requires the use of the words “It will be OK”, words, which when uttered by the newly bereaved can only be described as a lie.

Due to the scale and intensity of our communities’ supportive reaction, neither my parents or myself were ever alone with our uncertainty and fear from, effectively, the moment we first heard about the accident. We were quite literally surrounded by and rocked in the bosom of our community. It was a remarkable experience, and at the time I was quite uncritically pleased and grateful for it. Since then, while still deeply gratified by the outpouring of support and concern we experienced, my understanding of the reaction has become more complex and taken on a critical overtone.

I became quickly, if haphazardly, self-educated about, for example, head injuries, brain damage, and the experiences associated with serious accidents and death. i learned about the stages of grief, which are helpfully provided in convenient pamphlet form to persons awaiting word on their loved ones in the ICU’s counseling lounge, which is a private room used to provide a private environment for medical personnel and chaplains or representatives of faith to perform an essential part of their profession, that of grief counselor.

Because of the unique circumstances surrounding my sister’s crisis, my family became amateur grief counselors to a surprisingly large number of persons, not all of them the youth who first inevitably adopted her moment of desperate need as, appropriately, a learning experience. I want to stress that this is natural.

Thus, when I entered the waiting are in search of my parents, it was not I alone with my parents who dealt with my grief and loss – there were many others there as well, with many, heartbreaking questions. We answered them as best we could, and my parents and I must have retired to the private lounge to discuss and review.

The pressure test and EEG was on the other side of an infinite night stretching before us. Although I was certain my sister was dead, she could not be declared medically dead until an EEG had been performed; should the EEG reveal no brain activity, we would face a decision concerning the prolongation of life through artificial means. I was adamant. “Pull the damn plug!”, I practically shouted; my parents had discussed this among themselves and come to the same conclusions, thankfully.

And so we attempted to sleep. The lounge looked like an encampment of street people, black leather and combat boots under army blankets. Little subunits would venture off to smoke or get food and then return.

The pay phones in the waiting area rang constantly, for us, and for other distraught families.

Eventually, I believe the next morning, I answered the phone to hear the voice of a colleague of my father’s, a man I’d known since I was eleven or so, calling from an airplane. He had lost a child in a boating accident long, long ago, and I knew that the loss of that child has had a profound effect on his family ever since. His son, a few years older than I, is one of the greatest young American writers of the present day, and his talent has been hailed since he first began publishing in the late eighties, as I recall. It’s my firm belief that this writer’s fierce pursuit – courtship, even – of danger and death is partially related to the loss of his sibling.

I recall reading an article of his in a pop-culture magazine in which he journalistically recounted the experience of being a passenger in a car somewhere in the former Yugoslavia when it went over a land mine and killed the other occupants of the car, journalists with whom I believe he’d been working. Although he was unhurt physically, he recounted his wandering through the war-torn countryside in such a way as to make it clear how deeply affected he was by the event.

I was in an airport awaiting a friend’s arrival, and on reading this passage, I knew he flashed back to the death of his sister as he went into shock. I knew this irrationally, however. I knew it because on reading it I flashed back to my experience in the ICU, and to my experience of answering the phone to find his father on the line. The writer’s father, my dad’s colleague, attempted to speak to me and simply burst into great sobbing tears, repeating variations on “I’m so sorry”. I waited for him, and listened, and one thing he told me which I recall and which is true is that “It doesn’t go away. Time will cover it, but you’ll experience things in your life – as what’s happened to your sister is affecting me – that will bring it painfully anew to the surface of your psyche.”

Since that day, these words have come true again and again.

Eventually, my parents returned, and I was able to put my father on the phone with his friend. Let’s assume that they were off, attending the EEG. My mother told me that, as expected, there was no further electrical activity in my sister’s battered brain.

From here again, things are not clear in memory.

I attended my sister’s bedside with my parents, and, weeping, I cut a great forelock she’d grown and repeatedly cultivated as a fantastic item of plumage, dyeing and redyeing it, dredding it and coloring it with henna, cutting it off and regrowing it as she hung the dredd precursor from the handlebars of her bike.

Months later, miles from my parent’s house, I found the dredded handlebar ornament in the gutter by the sidewalk. I have no idea how it got there, but it was certainly hers, and I picked it up and retain it yet.

On September 18, 1988, we held a memorial service for my sister. My family practices cremation and has no graves; my sister’s body had already been consigned to the flames.

We stood in the warm September sun greeting people. If I recall correctly, a columnist for the local paper had written an article about the life and death of my sister which had been published that week, possibly (although it seems doubtful, really) on the bottom of the front page, for which I and several friends had been interviewed.

So we greeted them as they came in. We greeted my parents’ peers, and the congregation of our childhood church, and our friends from high school and from college. We greeted our teachers from high school, and from middle school. We greeted our professors from the university. We greeted fellow-students from IU, and former roommates, and co-workers, and the families of all of these people.

And still we greeted them. We greeted former lovers and ex-girlfriends and casual dates and people I sort of knew and people I didn’t know at all and their families.

And still we greeted them.

Finally, as the staff of the funeral home scrambled to set up more chairs, and still the line stretched around the building and snaked up the parking lot past the cars of people waiting to pull in and doubled back on itself, my father retired us from greeting; I think close relatives took over. The funeral home could not possibly contain them all. We were assured the PA could pipe the eulogies outside.

In my estimation, between 500 and 700, but possibly more, people attended. I honestly do not recall if the article was published prior to the memorial service or not. At any rate, I think that the mass of people represented three distinct social circles who had all been affected by the life of my sister. First, the immediate social group of my parents, constituted of church people and university people.

I’d estimate my parents’ extended peer network at about 300 persons. Then, my sister’s university, internationalist, and activist circle, again, a group with between 200-300 persons. Finally, the peer group my sister and I shared, what may be described as the bohemian community of Bloomington; again, this group numbered between 300 and 450 persons, in my estimation. Thus, our family’s moment of loss became a lightning rod for at least three distinct, thriving, well-populated social networks; her death became theirs to mourn as well.

I left Bloomington for Seattle in 1990, just as the Gulf War events were set in motion. I had (more or less) finished college (damn pesky French requirement rules change). I’ve been here ever since. My parents left Bloomington for Chapel Hill the same year. By about 1992, most of the people my sister and I grew up with had left Bloomington.

Between now and then, the circle of invulnerability around our shining youth abraded away. Brian and Robbie, each dead in different motorcycle accidents. Laird, lying in the soil at Puerto Vallarta. Heather, dead more awfully than i care to reflect on. Steve. Those of you I knew back then, I’m sure there’s plenty of others; those of you who’ve met me since, I’m sure you have your own dead.

They’ve been standing at your shoulder this week as you read this, every death you’ll ever experience; reading about my loss through your eyes, whispering in your ears of your own echoes of loss and the ways it’s warped and knotted the trunk of your life. You’ve grown over that barbed wire, or been bent by the wind, or sought the sun, and they live on in you, in your refractions of them and reflections upon them. Each time you animate them by taking their puppet of memory off the shelf, they’re really right there with you, not quite as before.

But there, and with you.

Raise a glass.

Repeat after me: “To absent friends!”

Drink.

(As I finish this, I smell my sister’s sweat. Perhaps it’s from the hair i scanned: her body oils on it moistened by my fingertips bloom a gift of scent to me. There are many good reasons for keepsakes.)

Her death dramatically changed my life, not entirely in positive ways. I treat those around me, most of the time, as though you might be dead tomorrow. Or so I’d like to think. Unfortunately for my morale, that means I engage in a great deal more anxious introspection than I did previously. On balance, though, I’d rather be kind to you than act thoughtlessly for my own gratification… Or so I’d like to think.

My lifestyle is much more conventionally bounded these days than it was at the time, as well. Today, you could take me home to your folks without worrying I’d drink all your liquor, flirt with your mom, or pick a political fight with your dad. I miss doing those things, but I’ve made my choice.

There are a few more pictures of my sister (sorry, no larger links behind them – perhaps later) at suzy.whybark.com. Reloading the page randomly loads another image. There are about ten images, I think.

Suzy (left) and Danielle, at the House of Ragin’ Women*, circa 1987. photo by Matt Uhlmann.

I should write more about her life now, but this has been quite a labor this week. I’ll close by noting that people were thoughtful enough to keep bringing items of personal significance even to the memorial service. Some have expressed their loss in other ways later, too.

Thanks to all of you who were their at the time, and thanks again to all of you who joined me for this long memoir of another sad September, a long time ago, when my world was young. Every September since then, I fall into a funk by the end of the first week, and it takes until around my Dad’s birthday, the 18th, to figure out why. This year, and presumably for the rest of my life, there will be more public grieving overlaying my own reactions to this damnable time of year. Next year, I will be, I think, better prepared for it.

*Yes, it was really called that, and yes, I know about Jaime’s excellent book. His came out shortly after the place was named; just coincidence.