The screaming of the aluminum girders suddenly ceased. The deep spanging thrum of cables popping slowed. Charles E. Rosendahl clung to a girder and watched the rear half of the great dirigible dwindle below him into the, uh, dark and stormy night.

The screaming of the aluminum girders suddenly ceased. The deep spanging thrum of cables popping slowed. Charles E. Rosendahl clung to a girder and watched the rear half of the great dirigible dwindle below him into the, uh, dark and stormy night.

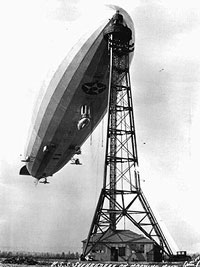

Rosendahl was the navigator on the USS Shenandoah, the first of the US Navy’s four great dirigibles. Reverse-engineered from a German zeppelin brought down over England, the major engineering innovation in the ship’s design was the use of helium, which, as we all know, is a good idea for an airship. Adding to the attractiveness of the idea, the United States at the time had a global monopoly on helium production.

The airship.freeserve.co.uk site has a gallery of collectors’ images of the Shenandoah. Navy Lakehurst Historical Society also has a great deal of Shenandoah-related material.

The Shenandoah (said to be an Algonquian word meaning “Daughter of the Stars”) had already survived at least two near-disasters in her mere 2 years afloat. She’d been in flight for about 24 hours, en route to St. Louis from her base at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The other incidents were both wind-related accidents. She’d been torn from her moorings in a New Jersey iwindstorm, losing her nose in the process and free-ballooning for the better part of a day all over the eastern seaboard before the 17 persons who happened to be aboard at the time were able to bring her home.

The Shenandoah (said to be an Algonquian word meaning “Daughter of the Stars”) had already survived at least two near-disasters in her mere 2 years afloat. She’d been in flight for about 24 hours, en route to St. Louis from her base at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The other incidents were both wind-related accidents. She’d been torn from her moorings in a New Jersey iwindstorm, losing her nose in the process and free-ballooning for the better part of a day all over the eastern seaboard before the 17 persons who happened to be aboard at the time were able to bring her home.

Her other brush with death happened when she was caught in downdrafts while crossing mountains in Arizona on her way to San Diego.

The first incident was widely publicized, with a commercial radio station (the beloved WOR) actually playing a key role in establishing communications with the wounded giant and broadcasting the radio link live to the greater metropolitan area of New York City (imagine!).

The night-time incident in the mountains was not widely covered.

On September 2, 1925, the Shenandoah had departed Lakehurst on the first leg of a Midwestern publicity tour. Publicity tours proved, for all of the Navy’s airships, to actually be the single most time-consuming missions the dirigibles would undertake. The popularity of the ships with the public and politicians, combined with a certain military impracticality, engendered a great deal of criticism of the LTA program within the Navy. Even within the LTA program, these goodwill tours were not regarded as pleasant or worthwhile assignments. The commander of the Shenandoah, Captain Zachary Lansdowne, is said to have been annoyed that the schedule for the airship’s Midwestern journey was published in advance.

This annoyance seems selfish and petulant at best to modern ears. In researching this article and from other readings in the area, it’s clear that the presence of one of these ships in the sky over your city or farm was regarded as an event of great moment. People took time off work, made plans to rise in the middle of the night, and then talked about the sight for the rest of their lives. Much like the space program of the 1960s, the technology of the airship appears to have offered a sort of totem for utopian ideals of technological and social progress.

At any rate, it’s well documented that all along the route the ship was scheduled to take, from Lakehurst to St. Louis, people were aware that the ship was coming and had made plans to be outside looking for the ship when she flew over. For the people of Noble County, Ohio, this anticipation would turn to something very different a little past 4 o’clock on the morning of September 3.

Navigator Rosendahl noted a cloud formation that might be a storm front at 4:20 am, and brought it to the attention of Captain Lansdowne. At the same time, the ship began to rise uncontrollably. This initial rise carried the ship to 3,100 feet, where severe turbulence was encountered. A second, faster rise occurred, carrying the ship to a height of over 6,000 feet despite emergency venting of helium.

The crew of forty-three, roused by the turbulence and the dramatic changes in air pressure, were all working to secure the ship. They were quite aware that an uncontrolled ascent posed a grave threat to the gas cells, which could rupture if the ship were not brought under control.

The crew of forty-three, roused by the turbulence and the dramatic changes in air pressure, were all working to secure the ship. They were quite aware that an uncontrolled ascent posed a grave threat to the gas cells, which could rupture if the ship were not brought under control.

On the ground, observers recount seeing the ship tumbled along a mass of scudding cloud in the moonlight and suddenly shot high into the sky. As suddenly as it lifted, it was seen to dive dramatically.

Aboard, the crew felt a cold wind catch the ship, and as the ship moved from the rapidly ascending column of warm air and entered the rapidly dropping column of cold air, the efforts to vent gas were replaced by orders to dump ballast. As the crew’s frantic efforts yielded a short-lived artificial rainstorm of seven thousand gallons of water onto the Ohio soil, she entered another thermal column.

Navigator Rosendahl was sent aft. As he headed toward the rear of the ship, she assumed a violently inclined position, possibly nose up. In essence, the front of the ship was in one weather system, and the rear was in another. The collision of the fronts created sufficient windshear that the ship was literally torn in two. Rosendahl stood at the breach, riding the nose of the divided ship skyward.

When the break occurred, the nose-mounted control car, containing the bridge and the captain, was torn away from the hull and plummeted about three thousand feet to the ground. Engines along both main sections of the hull fell away as well, carrying with them mechanics who had climbed out to tend them in the fantastic beating the ship had been taking.

The bow section rose into the turbulent night. Rosendahl and six other airmen established contact with one another and took stock of their grim situation as the undamaged helium cells lifted the bullet-shaped wreck high above the Ohio countryside, reaching an estimated height of 10,000 feet.

The aft section, about 470 feet of the 680-foot ship, broke once more before landing close to the location of the control car’s impact.

Meanwhile, local residents had begun to stream toward the grounded remnants of the once-proud ship, and as the stunned survivors of the wreck sought both care and contact with the Navy, news spread rapidly, eventually drawing an estimated (by me) ten thousand people to the wreck sites within a couple of days of the event. The wrecks were stripped by souvenir seekers, although a guard was eventually posted.

I’ve seen photos of unconcerned looking guards before sections of the wreck that have clearly not been picked over, and read accounts of picking so thorough that souvenir hunters dug up potatoes from the farms the hull landed atop when there was no material to be had from the broken body of the Shenandoah.

As Noble County began to react to the historic tragedy unfolding above, the seven remaining fliers systematically began to bring the remnant of the Shenandoah under control, principally by venting helium. An hour after the breakup and twelve miles away, they were low enough to call out to farmer Ernest Nichols for help securing one of the trailing cables.

In a Cleveland Plain Dealer article, “Dirigible disaster“, one of several elderly eyewitnesses reminisces:

The farmer’s son, Stanley E. Nichols, 77, of Caldwell, was only 2 ½, but said he vividly remembers when that giant silver cone, nearly 10 stories high and 300 feet long, came plowing through their orchard.

“I was scared. We were all scared. Very scared,” Nichols said. “It was coming right at us, open-end first, with long strips of fabric flapping in the wind.”

(The article includes an elderly woman recalling the ship coming apart in the air, as well.)

Nichols gave it a shot, busting a fence and uprooting a tree stump in the process before finally setting the rope to a large tree. The seven shaken survivors then borrowed the farmer’s shotgun and holed the remaining helium cells, laying the Shenandoah to her rest. Remarkably, only fourteen persons perished, eleven of those in the control car.

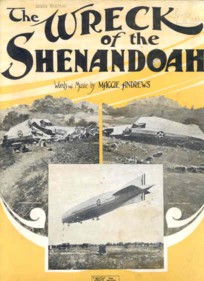

Her last flight might have been over, but the consequences of the wreck had just begin. A song, “The Wreck of the Shenandoah” was written and released under the pen name “Maggie Andrews” by the team of Carson Robison and Vernon Dalhart, who specialized in disaster ballads and are remembered today principally for “The Wreck of the Old 97”. A recorded version of the song was also released, but both versions were quickly suppressed after complaints from family members of those lost in the incident (click the image of the sheet music for a large view of both sections of the wreck).

Her last flight might have been over, but the consequences of the wreck had just begin. A song, “The Wreck of the Shenandoah” was written and released under the pen name “Maggie Andrews” by the team of Carson Robison and Vernon Dalhart, who specialized in disaster ballads and are remembered today principally for “The Wreck of the Old 97”. A recorded version of the song was also released, but both versions were quickly suppressed after complaints from family members of those lost in the incident (click the image of the sheet music for a large view of both sections of the wreck).

I’d hoped to find a recording of the song to link to, or failing that, to perform the song and provide that here, but I was unable to locate the music in time for this article. I did find a link to a “school paper” preserved by the family of one Dalton McLaughlin, possibly in the belief that Mr. McLaughlin had written the lyrics, but which are probably a child’s transcription of the song.

An additional, and not at all obvious consequence of the wreck, was the loss of all the US Navy’s helium. Helium was dramatically more expensive than hydrogen (over $100 a cubic foot versus hydrogen’s $2-and-change), and although the Navy had two active dirigibles in service in September of 1925, (the Los Angeles had been delivered from Germany in October of 1924) but helium was so scarce that only one of the two ships could be airborne at a time. It would be April of 1926 before there were sufficient helium reserves available for the ship to take to the skies once again.

The wreck is still recalled today, as the Plain Dealer article referenced above shows, and I also located an article at the New England Aviation Museum which includes photos of the wreck site from 1997 and from 1925. Bryan Rayner, of Ava, Ohio, the town closest to the wreck, maintains a museum in a trailer with wreck-related artifacts and curiosities.

Finally, here’s another account of the airship’s loss, originally published in American Heritage in 1969: The Death of a Dirigible. It’s much more dramatic than mine.

UPDATE: I followed up some on the Vernon Dalhart song here, and there are some other wonderfully interesting comments on that entry as well.

UPDATE, 2008: Gregg Frisby has sent some family photos of the tail section, probably taken early on the morning of the wreck.

I awakened this morning to the familiar voice of Susan Stamberg introducing a feature on one of my favorite places in the world – San Francisco’s

I awakened this morning to the familiar voice of Susan Stamberg introducing a feature on one of my favorite places in the world – San Francisco’s  Together, the two venerable survivors of the first part of last century provide an opportunity to experience a bit of time travel: to the turn of the century, on the one hand, and into the renaissance on the other.

Together, the two venerable survivors of the first part of last century provide an opportunity to experience a bit of time travel: to the turn of the century, on the one hand, and into the renaissance on the other.

Restored in a building campaign intended in part to compete with the New York World’s Fair of 1939, MSI benefited from the commercial failure of the Fair by hiring many exhibit designers, and, I very strongly suspect, by purchasing entire exhibits when the Fair was closed and dismantled in 1941.

Restored in a building campaign intended in part to compete with the New York World’s Fair of 1939, MSI benefited from the commercial failure of the Fair by hiring many exhibit designers, and, I very strongly suspect, by purchasing entire exhibits when the Fair was closed and dismantled in 1941.